- Share via

The name Venezuela is everywhere these days, as thousands of nationals grapple with immense challenges in the United States — from the looming threat of losing Temporary Protected Status, a threat put temporarily on hold by a Californian judge, to nationals who have been sent to a prison in El Salvador without due process.

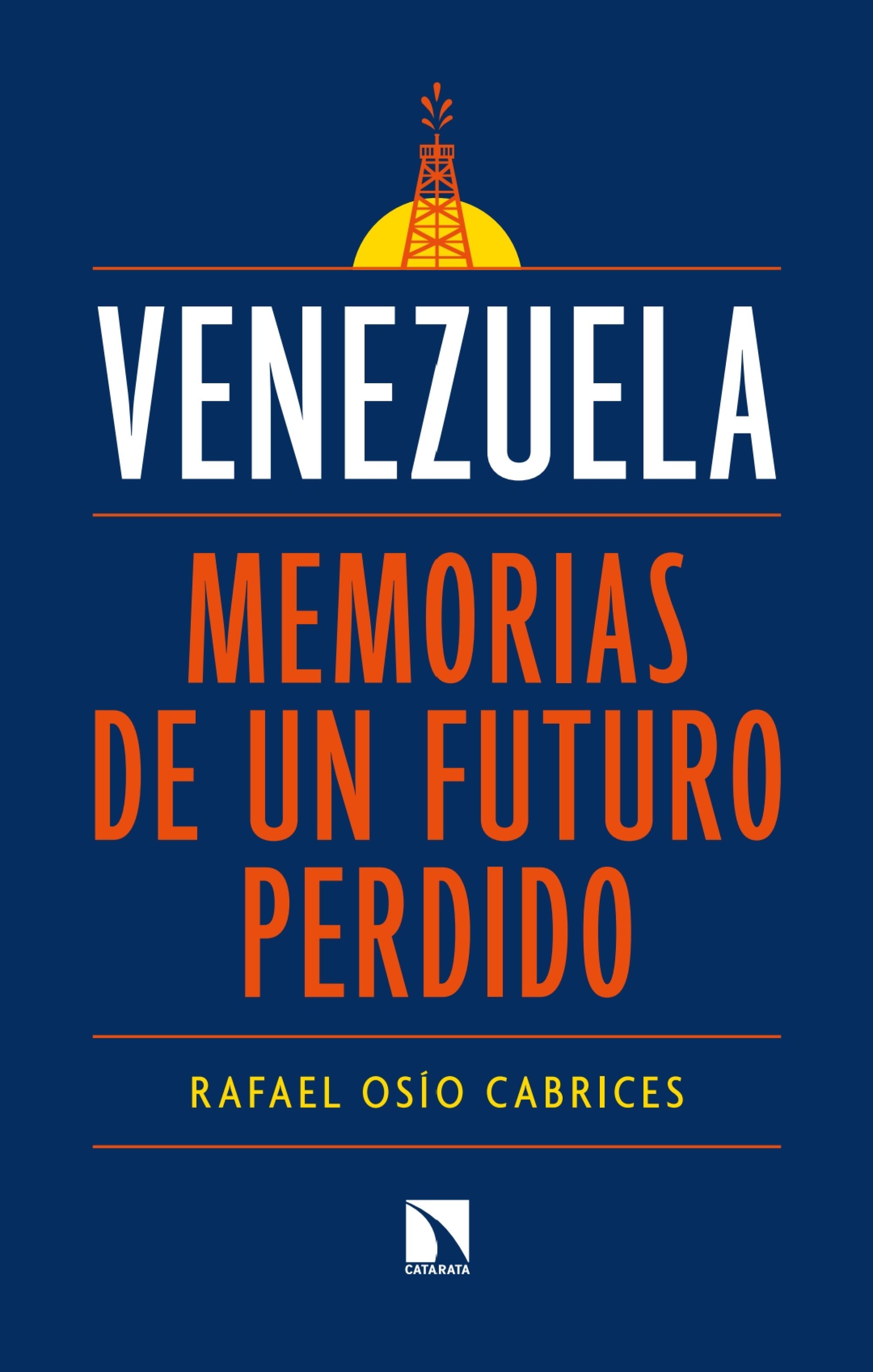

Rafael Osío Cabrices is a seasoned Venezuelan journalist with over 30 years of experience who currently resides in Montreal, Canada. He is the author of “Venezuela. Memorias de un Futuro Perdido” (“Venezuela. Memories of a Lost Future”), published in 2024 by Los Libros de la Catarata. The book chronicles the events that led to the country’s catastrophic socioeconomic crisis and explores the hopeful future that Venezuelans failed to attain in their land. Narrated like a close friend would — with brutal honesty and the emotions of lived experiences — the book provides the inquisitive perspective of a reporter eager to understand the connections that created that reality.

“I didn’t know I had this book in me. I was busy writing a novel about [Venezuela’s first president, José Antonio] Páez,” Osío Cabrices said in Spanish. “Then, a friend told me that this publisher in Spain wanted to talk to me because they wanted to publish a book about Venezuela.”

He says he thought at first that they were merely seeking his advice on who should write it, but later realized that he was the one they had reached out to.

The writing process took 18 days — an unthinkable timeframe for completing a book. Osío Cabrices says it was challenging not only because of the long nights and intellectual exhaustion that came from writing, but also because of the emotional burden of revisiting some of the nation’s most violent and devastating moments and their personal repercussions.

“I had rekindled painful memories all at once,” explained the writer. “I have never done anything as personal as this before.”

In the book, Osío Cabrices recounts the last visit to his father on the island of Margarita in 2018, a place that was once a vibrant paradise where people basked in the warmth of the Caribbean sun and indulged in duty-free shopping. By then, however, it had transformed into a silent desert of empty houses. His father’s words lingered in the air: “You can’t hear the parties anymore […] You can’t even smell the grills, and this is Margarita. There are no more young people here.”

It was a painful farewell, though he did not yet know it would be the last. Two years later, his father passed away, and he didn’t have the chance to see him again or even attend his funeral.

“Defending democracy was not among the priorities: it had fallen on the list of old junk to be removed from the house in the total clean-up operation that seemed to be the spirit of the moment,” he writes in the book, referring to the nature of the Venezuelan 1990s. Nonetheless, in the current U.S. political climate, this sentiment feels oddly familiar.

Osío Cabrices argues that people nowadays are not very aware of what democracy means and why its preservation is important, adding that “this is one of the great diseases of the present.”

At the heart of his writing is the idea of providing a deeper and more nuanced understanding of a country that lost a quarter of its population in less than a decade — one that goes beyond the images of humanitarian emergencies, crime, repression and economic collapse.

While he recognizes the differences between his country and the U.S., he also acknowledges that the Venezuela’s case illustrates how a society that has done many things well can make wrong decisions and destroy everything it built. He argues that democracy can’t be taken for granted and that it’s not like adulthood, a stage you reach that you don’t leave.

“It’s like building a Jenga [tower] that any mistake you make can collapse what you’ve built and upend your life,” he stressed.

Venezuela is a word with a profound and complex meaning for both its people and foreigners. As Osío Cabrices put it in his book, “Behind those four syllables, beauty and horror squeeze together.” It embodies the paradox of a place that one can love and fear at the same time — where the “most beautiful sunset on the planet” exists side by side with the undeniable reality that the most terrible things can also unfold.

“Venezuela is in a very bad shape, but it is not dead [...] Instead of giving up on it, we have to take a closer look at it, call things by their name, tell its story — our own stories — with the precision, anger, affection, sensuality, volume, and respect that they deserve.” he writes.

De Los Reads April picks:

Precious Rubbish (Fantagraphics, April 2025), by Kayla E.

This cathartic graphic memoir delves into childhood trauma, poverty and abuse, weaving a deeply personal story through the enticing style of mid-century comics. As the author describes it, “If an exorcism can ever be slow and quiet, then every panel I’ve finished has felt something like an exorcism.”

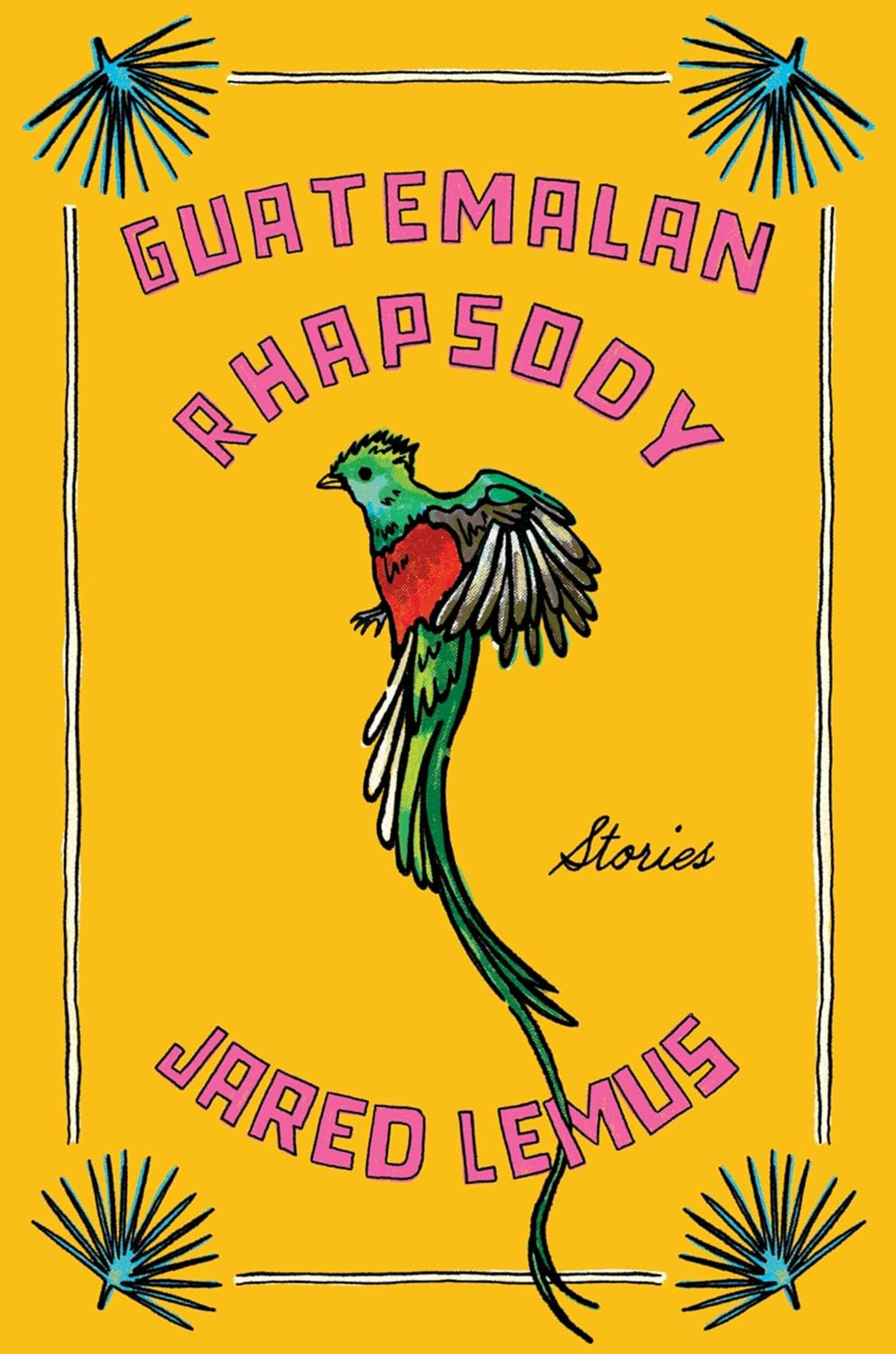

Guatemalan Rhapsody (Ecco, March 2025), by Jared Lemus

Dark at moments yet pulsing with resilience, this debut collection of stories follows characters trapped in dire circumstances, each seeking to escape through unconventional and sometimes unsettling means. It is a haunting exploration of survival and transformation.

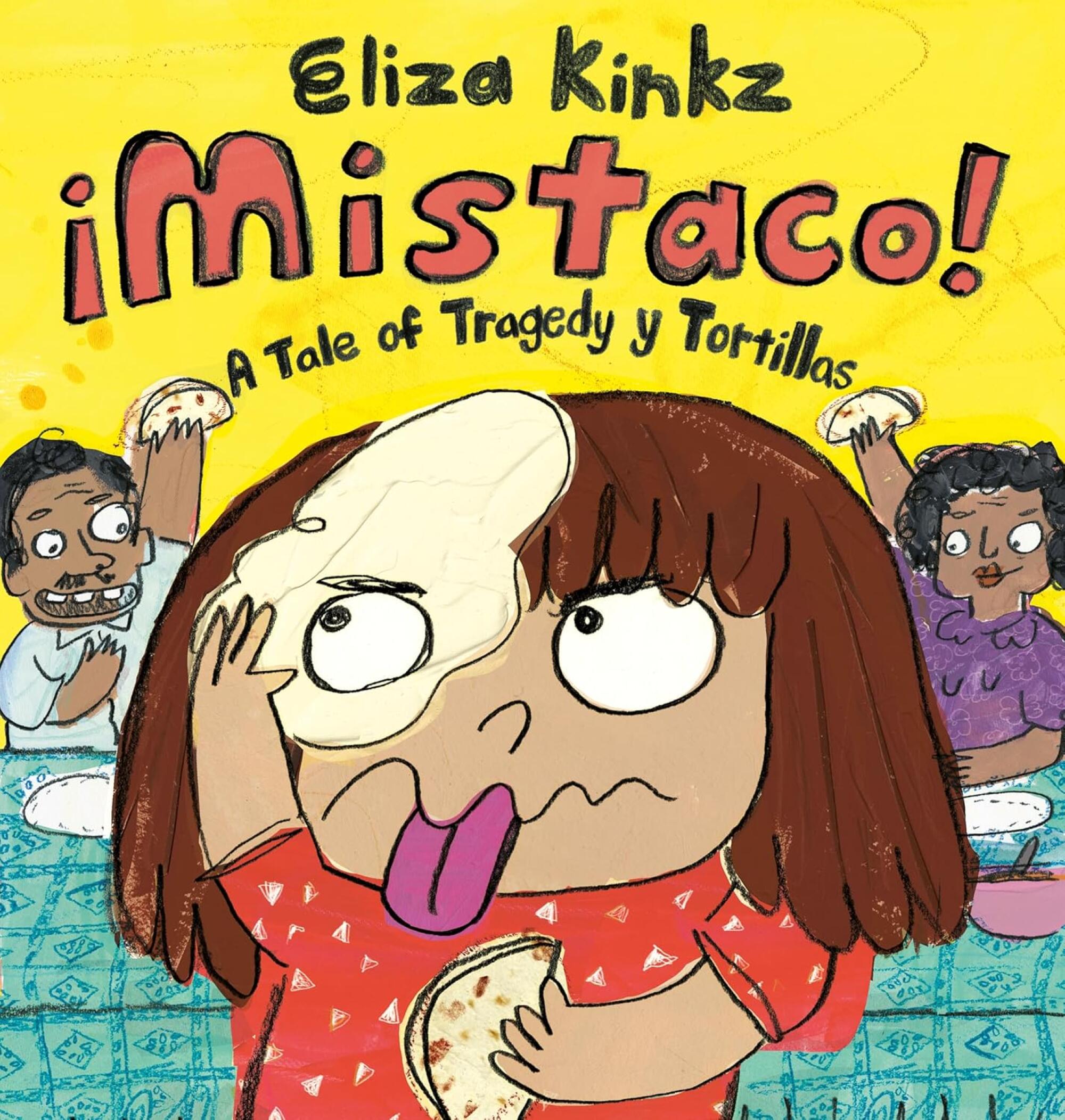

Mistaco (Kokila, April 2025), by Eliza Kinkz

Little Izzy’s worst nightmare is making mistakes — everywhere, all the time. But when it’s time to make tortillas with family, there’s no such thing as messing up. Even if a tortilla turns out looking like “a donkey kicking a potato,” nothing can stop them from creating the most delicious memories. With hilarious illustrations, this picture book is the perfect recipe for a fun-filled afternoon.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.